| Informed Consent in Clinical Trials |

|---|

| Informed consent in clinical trials is an ongoing process where participants are clearly informed about the study purpose, procedures, potential risks, expected benefits, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. |

Every clinical trial begins with a single non-negotiable requirement: informed consent.

Before a participant can be screened, tested, or exposed to any study-related procedure, their voluntary and informed agreement must be obtained and documented. This is not an administrative formality. It is the ethical and legal foundation of clinical research.

Without valid informed consent, a clinical trial cannot proceed, no matter how well designed the protocol is or how promising the investigational treatment may be. Failures in the consent process have repeatedly led to trial suspensions, regulatory action, and loss of public trust. This is why informed consent is treated as a core ethical responsibility in clinical research, not just a signed document.

What Is Informed Consent in Clinical Trials

In clinical trials, the informed consent process means that a participant clearly understands what a study involves and agrees to take part voluntarily. Before joining a trial, the participant is informed about the study’s purpose, what procedures will take place, the possible risks and benefits, and their right to refuse or withdraw at any time. Only after this information is clearly understood can a participant make an informed decision to participate.

In simple terms, this explains the informed consent process and how it is applied in real clinical trial settings as an ongoing communication process rather than just a signed form.

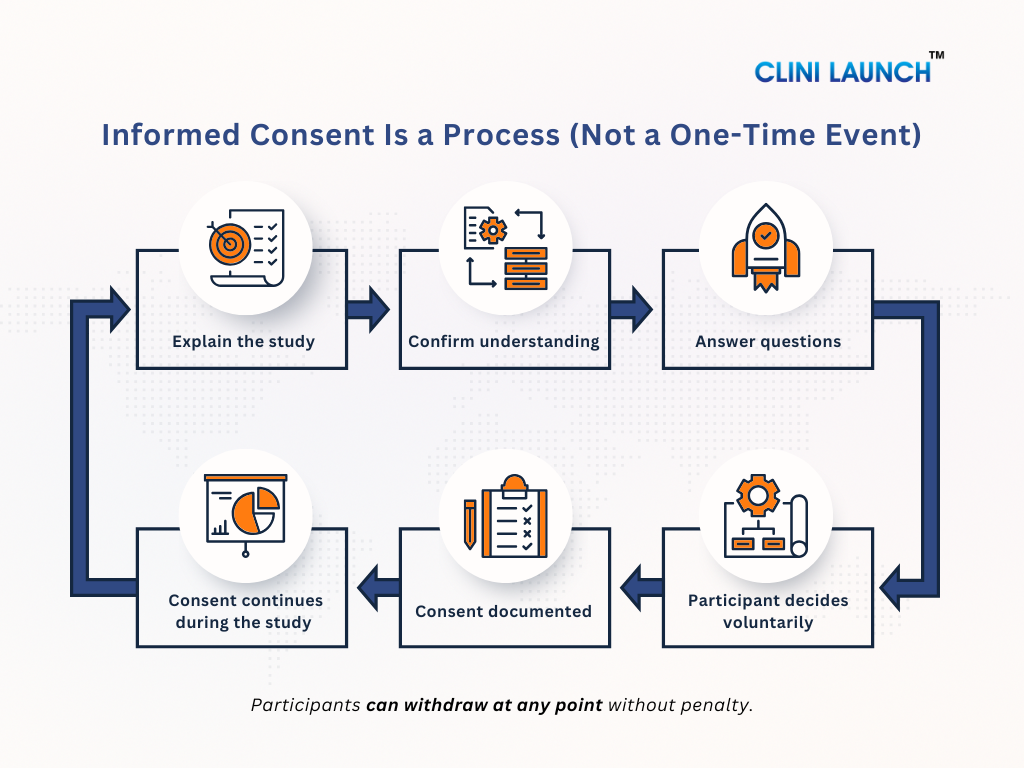

Informed Consent Is a Process, not a Signature

Many people think informed consent is just signing a form. This is not true. Informed consent is an ongoing process. It starts when the study is first explained and continues throughout the trial. Participants should always be kept informed. If anything changes in the study or new risks are found, the participant must be told again and given a chance to decide whether they still want to continue.

The 3 Core Requirements of Informed Consent

For informed consent to be valid in a clinical trial, it must meet three essential requirements. If even one of these is missing, the consent is considered incomplete. These requirements are central to the informed consent definition used in ethical clinical research.

1. Voluntary

Consent must be given freely and without pressure.

The participant should never feel forced, rushed, or afraid to say no.

This means:

- Participation is optional

- Saying no will not affect medical care

- The participant can leave the study at any time

For example, a participant should not feel that joining the trial is the only way to receive treatment or medical attention. True consent exists only when the decision is made by choice.

2. Understandable

The information shared must be easy to understand.

Using complex medical terms or speaking too fast can prevent real understanding.

This means:

- Information should be explained in simple language

- Medical jargon should be avoided or clearly explained

- The participant should be encouraged to ask questions

Understanding is not assumed just because someone signs a form. Researchers must make sure the participants truly understand what the study involves.

3. Informed

The participants must receive complete and honest information about the study.

This includes:

- Why the study is being done

- What will happen during the study

- Possible risks and side effects

- Possible benefits (or lack of direct benefit)

- Other treatment options available

Consent is considered informed only when the participant has enough information to make a thoughtful and confident decision.

Clinical Research

Build industry-ready skills to work across real clinical trial environments, from study initiation to close-out. Learn how clinical research actually operates in hospitals, CROs, pharma companies, and research organizations, with a strong focus on compliance, documentation, and trial execution.

Duration: 6 months

Skills you’ll build:

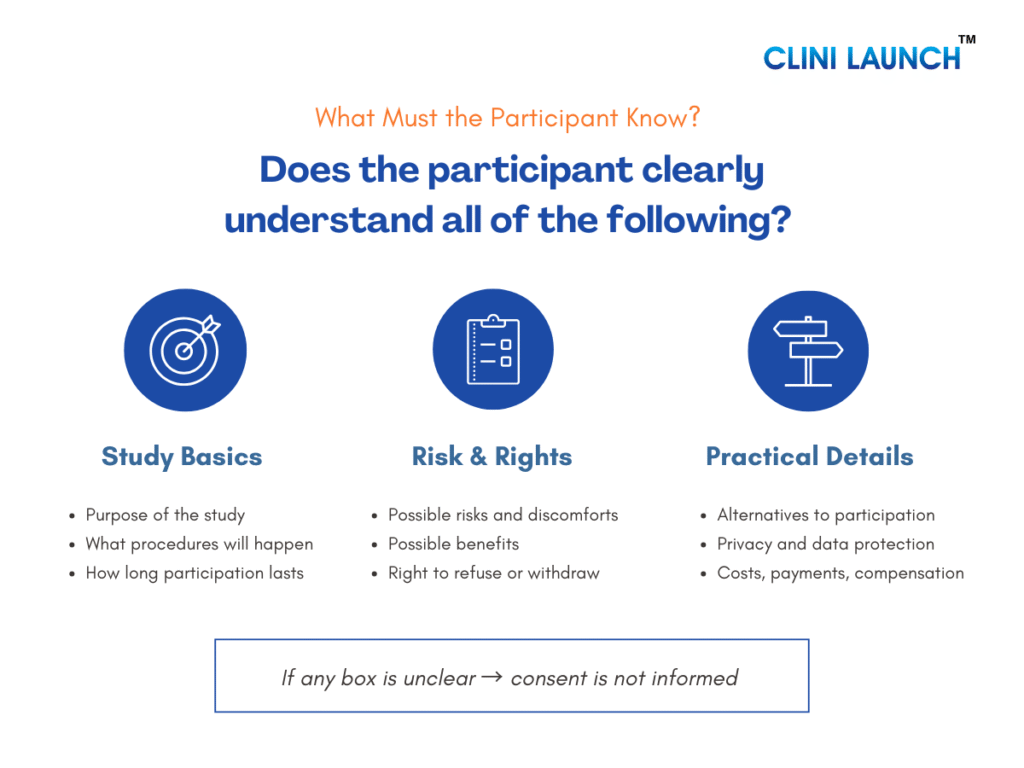

What Participants Must Be Told During Informed Consent

For informed consent to be valid, participants must be clearly told about certain essential information before they agree to join a clinical trial. This ensures they can decide with confidence, clarity, and without pressure.

- Purpose, Duration, and What Will Happen

Participants must be told:

- Why the study is being done and what question it aims to answer

- How long the study will last, including follow-up periods

- What exactly will happen to them, such as clinic visits, tests, treatments, or sample collection

This helps participants understand the level of involvement required and decide whether the study fits their personal and medical situation.

- Risks, Discomforts, and Possible Benefits

Participants must be informed about:

- Possible risks and side effects, even if they are uncommon

- Any physical, emotional, or practical discomfort they may experience

- Possible benefits, if any, and whether there may be no direct benefit to them

Risks must be explained honestly and clearly so participants can balance potential harm against possible benefits before deciding.

- Alternatives to Participation

Participants must be told:

- Other available treatment or care options

- That choosing not to participate will not affect their access to medical care

This ensures participants do not feel pressured to join the study or believe it is their only option.

- Privacy, Confidentiality, and Data Use

Participants must understand:

- How their personal and medical information will be collected and stored

- Who may access their data, such as researchers or regulatory authorities

- How their identity will be protected as far as possible

These build trust and reassure participants that their personal information will be handled responsibly.

- Costs, Compensation, and Treatment for Injury

Participants must be told:

- Whether there are any costs related to participating in the study

- If compensation or reimbursement is provided for time or travel

- What medical care or compensation is available if a study-related injury occurs

Clear communication in this area helps prevent confusion or disputes later.

- Right to Refuse or Withdraw Without Penalty

Participants must be clearly told that:

- Participation in the study is completely voluntary

- They can refuse to participate without giving a reason

- They can withdraw from the study at any time without losing medical care or benefits

This reinforces participant’s autonomy and ensures they remain in control of their decision.

- Whom to Contact for Questions and Emergencies

Participants must be given:

- Contact details of the study investigator or study team

- Information on whom to contact for general questions

- Emergency contact details for urgent situations

This ensures participants know where to seek help or clarification at any stage of the study.

How the Consent Process Works in Real Clinical Trials

In real clinical trials, informed consent is not a one-time formality. It is a structured, step-by-step process designed to protect participants before they join a study and while the study is ongoing. Regulatory authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration clearly state that informed consent must be obtained before any study-related activity begins and must continue throughout the trial. This section shows informed consent processes in real clinical trials, beyond theory and documentation.

1. When Consent Happens — Before Any Study Procedure

In clinical trials, informed consent must be obtained before:

- Any screening tests

- Any study-related examination

- Any trial medication or intervention

- Any data or sample collection

The study team explains the study in detail, answers questions, and ensures the participant understands the information. Only after this discussion does the participant sign the informed consent form. If any study procedure happens before consent, the consent is considered invalid.

| When Consent Comes Too Late: India’s 2010 Clinical Trial Crisis |

|---|

|

In the early 2010s, serious concerns emerged in India regarding how clinical trials were conducted. Reports indicated that some participants were enrolled without fully understanding the study, and in certain cases, informed consent was obtained only after study-related procedures had already begun.

These concerns reached the Supreme Court of India through a public interest litigation filed by Swasthya Adhikar Manch, an organization advocating for patient rights. The court examined whether trial participants were adequately informed before being exposed to investigational drugs or procedures. The findings were significant. In 2013, the Supreme Court halted approvals for new clinical trials until stricter safeguards were established. A key issue identified was the failure to obtain valid informed consent prior to any study procedure. This case reinforced a fundamental principle of clinical research: consent obtained after a procedure is not considered valid informed consent. The outcome reshaped India’s clinical trial oversight framework and demonstrated how failures in informed consent can lead to major legal and regulatory intervention. |

2. “Key Information” Upfront — What Matters Most First

In real consent discussions, participants are first given key information that directly affects their decision, such as:

- Why the study is being conducted

- What will happen to them

- Major risks and possible benefits

- The voluntary nature of participation

This information is presented before lengthy technical details, so participants can quickly understand what truly matters and decide whether they want to continue learning about the study.

| When Key Information Is Not Told First: The Coventry Chapati Study |

|---|

|

Another important lesson in informed consent comes from the United Kingdom. In a nutrition study conducted in Coventry, South Asian women were given chapatis containing a radioactive iron isotope to examine iron absorption. Although consent documentation existed, later reviews identified a serious ethical failure.

Many participants were not clearly informed at the outset that radioactive material was involved. The true nature of the study and its potential risks were not explained in a manner the participants could easily understand. Critical information was either minimized or not communicated clearly at the beginning of the consent process. This study later became widely cited in bioethics discussions because it demonstrated that informed consent fails when key information is hidden, delayed, or deprioritized—even if a consent form is signed. The Coventry Chapati Study reinforced a fundamental principle of ethical research: participants must receive the most important information first—study purpose, procedures, and risks—before secondary details or paperwork. The case continues to be referenced as a clear example of why transparency at the very start of the informed consent process is essential. |

3. Ongoing Consent During the Study

Informed consent does not end once the form is signed. During the study:

- Participants may ask questions at any time

- New risks or safety findings must be shared

- Protocol changes may require re-consent

- Participants must be free to reconsider and withdraw

This ensures that consent remains informed and voluntary throughout the study, not just at the beginning.

| When Consent Is Treated as a One-Time Event: HIV Trials in Uganda |

|---|

|

A different type of informed consent failure was observed in HIV clinical trials conducted in Uganda. In these studies, participants signed informed consent forms correctly at the time of enrollment, and on paper, the consent process appeared compliant with regulatory requirements.

However, follow-up assessments of participant understanding revealed significant gaps over time. Many participants did not fully understand the study as it progressed. Some were unclear about their right to withdraw, while others misunderstood ongoing study procedures and expectations. Contributing factors included language barriers, low literacy levels, and long study durations. Without repeated explanations and reinforcement, participant understanding gradually declined. Researchers concluded that a single consent discussion at the beginning of the trial was insufficient. This led to an important principle in modern clinical research: informed consent is an ongoing process. Participants must be given continuous opportunities to ask questions, receive updates, and reconfirm their willingness to participate—especially when new information or changes arise during the study. |

Documentation and Formats in the Informed Consent Process

In clinical trials, informed consent must be documented properly to show that a participant understood the study and agreed to take part before any study procedure began. Proper documentation supports the informed consent form and compliance with ethics committee (IEC/IRB) requirements.

1.Written Consent and Signatures

- The study is explained to the participant

- The informed consent form is signed and dated

- The investigator also signs the form

This signed document is the official proof of consent.

It confirms that consent was taken correctly and on time.

2.Witness or Translator (When needed)

- Used when a participant cannot read or understand the consent form

- A translator explains the study in the participant’s language

- A witness confirms the explanation and signs

This ensures that consent is truly understood.

It protects participants from agreeing without understanding.

3.Electronic Informed Consent (eConsent)

- Consent is taken digitally using a tablet or computer

- May include videos or simple explanations

- Digital signatures and timestamps are recorded

This helps reduce paperwork errors and improves understanding.

It makes the consent process clearer and more reliable.

Medical Coding

Develop skills in clinical documentation, medical records analysis, and compliance practices that support ethical patient care and informed consent processes across healthcare and research settings. This program focuses on accuracy, standards, and real-world documentation workflows.

Duration: 6 months

Learn at your own pace

Skills you’ll build:

Other Courses

Special Situations Beginners Must Know in Informed Consent

In real clinical trials, informed consent does not always happen in a simple situation where an adult participant reads a form and signs it. Certain special situations require extra care to protect participants and ensure that consent remains ethical, valid, and fair.

1.Legally Authorized Representative (When a Participant Can’t Consent)

Sometimes, a participant is unable to give informed consent on their own, such as:

- When the participant is unconscious

- When there is severe cognitive impairment

- When the participant is critically ill

In these situations, consent is obtained from a Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) usually a close family member or legal guardian, as permitted by law. Guidance from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services makes it clear that this option is used only when the participant truly cannot decide for themselves.

The LAR is expected to act in the best interest of the participant, not for convenience or speed.

2.Assent for Minors

Children cannot legally provide informed consent on their own. When clinical research involves minors:

- Consent must be obtained from a parent or legal guardian

- The child’s assent (agreement) should also be sought, when appropriate

Assent means explaining the study to the child in age-appropriate, simple language and respecting their willingness or refusal to participate. Ethical guidance from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services emphasizes that children should be involved in the decision as much as they are able to understand.

3.Vulnerable Participants and Undue Influence

Some participants may be considered vulnerable, such as:

- Economically disadvantaged individuals

- Patients’ dependent on doctors, caregivers, or institutions

- Individuals with limited education or low health literacy

In these cases, extra safeguards are required to ensure participation is truly voluntary. Guidance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration stresses that consent must not be influenced by fear, authority, financial pressure, or promises of better care.

Participants must clearly understand that saying “no” will not affect their treatment or benefits.

4.Waiver, Alteration, and Emergency Exceptions (High-Level)

In rare situations, informed consent requirements may be waived or altered, such as:

- Certain minimal-risk research

- Emergency situations where immediate medical action is required

These exceptions are strictly controlled and allowed only with ethics committee approval and under regulations outlined in the eCFR. Consent is not ignored; it is adjusted only when participant’s safety or urgent public health needs require it.

5.Re-Consent After Protocol Changes or New Risk Information

Informed consent is an ongoing process, not a one-time event. If:

- The study protocol changes

- New risks are identified

- New information affects participant safety

Participants must be informed again, and re-consent may be required. Guidance from the ICH makes it clear that participants have the right to reconsider their participation when new information emerges.

| Key Takeaway for Beginners |

|---|

|

Informed consent is about protecting people, not paperwork.

Even in special or complex situations, consent is never skipped. Instead, it is adapted to ensure fairness, understanding, and respect. This may involve consent from a legally authorized representative, support through a child’s assent, additional safeguards for vulnerable participants, adjustments in emergency settings, or repeating consent after study changes. Regardless of the situation, the objective remains the same: participants must always have a meaningful choice about whether to take part in the research. |

Common Consent Mistakes (And Why They’re Serious)

In clinical research, informed consent usually fails not because of bad intent, but because of small, routine mistakes. For beginners, it’s important to recognize these mistakes early, because even simple errors can make consent ethically invalid and create serious regulatory issues. Many of these mistakes arise from misunderstanding the difference between consent and informed consent.

- Using “Too Technical” Language and Poor Understanding

One of the most common consent mistakes is explaining the study using complex medical or scientific language that participants cannot easily understand.

This typically happens when:

- Consent forms are written like scientific or regulatory documents

- Medical terms are not explained in simple language

- The study is explained quickly without checking understanding

Regulatory expectations under the eCFR require that consent information be understandable to the participant. If a participant does not truly understand what they are agreeing to, the consent is not considered informed even if the form has been signed.

- Coercion, Pressure, or Misleading Promises

Another serious mistake is influencing participants through pressure, authority, or misleading information, rather than allowing them to decide freely.

This can occur when:

- Doctors or study staff unintentionally pressure participants

- Participants fear losing medical care if they refuse

- Benefits are exaggerated or described as guaranteed

Guidance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration clearly states that informed consent must be voluntary and free from coercion or undue influence. If a participant agrees because they feel pressured or misled, the consent is no longer voluntary and therefore not valid.

- Missing Key Elements or Using the Wrong Consent Version

Consent can also fail due to documentation and version-control errors, even when the study has been explained properly.

Common examples include:

- Missing participant or investigator signatures

- Missing dates on the consent form

- Use of an outdated or unapproved consent version

Regulations require that only the current, ethics committee approved consent form is used. Even when participant’s understanding is adequate, incorrect or incomplete documentation can lead to serious findings during audits and may invalidate the participant’s consent.

Roles Where Consent Knowledge Is Non-Negotiable

In clinical research, informed consent is not handled by a single role. Different professionals interact with the consent process at different stages of a trial. For some roles, consent knowledge is part of daily responsibilities; for others, it is essential for verification, documentation, and oversight. In all cases, gaps in consent understanding can lead to ethical and compliance issues.

| Role | How the Role Interacts with Informed Consent |

|---|---|

| Clinical Research Coordinator (CRC) | Explains the study to participants, ensures the correct consent version is used, confirms that informed consent is obtained before any study procedure, and manages re-consent when required. |

| Clinical Research Associate (CRA) | Reviews informed consent forms during monitoring visits, checks signatures, dates, and version control, and verifies that consent was obtained before study-related procedures. |

| Research Nurse | Supports consent discussions with clinical explanations, identifies participant confusion or concerns, and flags situations where re-consent may be necessary. |

| Clinical Trial Assistant (CTA) | Maintains and files informed consent documents, tracks approved consent versions, and supports audits and inspections related to consent records. |

Why This Matters Across All Roles

Informed consent failures are rarely caused by one individual. A single consent issue often results from multiple small gaps across roles incomplete explanations, missed checks, or documentation errors. When consent knowledge is shared and understood across the team, participant rights are better protected and trial integrity is maintained.

Conclusion

Informed consent is where ethical intent is tested in real clinical practice. It is the point at which regulations, human judgment, communication skills, and accountability intersect. When handled correctly, it protects participants and preserves the credibility of the research. When handled poorly, it exposes trials to ethical failure, regulatory action, and lasting damage to public trust.

For anyone entering clinical research, informed consent is not just a topic to understand, but a responsibility to uphold. It shapes how studies are conducted, how participants are treated, and how confidently a trial can stand up to scrutiny. This is why we at CliniLaunch Research Institute treat this as a foundational competency in our clinical research training programs and not as a procedural checklist.

Learning the informed consent process early builds the mindset required for ethical decision-making, regulatory compliance, and participant-centered research—skills that define competent clinical research professionals across roles and settings.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the informed consent process in clinical research?

The informed consent process is an ongoing communication process where participants are informed about a study and voluntarily decide whether to take part.

2. What is the difference between consent and informed consent?

Consent is simply agreeing, while informed consent means agreeing after fully understanding the study, risks, benefits, and participant rights.

3. Who is responsible for obtaining informed consent in a clinical trial?

Informed consent is usually obtained by the investigator or trained study staff responsible for explaining the study to participants.

4. Is informed consent a one-time signature or an ongoing process?

Informed consent is an ongoing process that continues throughout the study, especially when new information or risks arise.

5. What information must be included in an informed consent form?

An informed consent form includes study purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, alternatives, privacy details, and the right to withdraw.

6. Can a participant withdraw from a clinical trial after giving consent?

Yes, participants can withdraw from a clinical trial at any time without penalty or loss of medical care.